As promised, this is a second collaboration with the history-focused Substack Notes From The Past. And yes, this one was inspired by late summer “controversies” around Tucker Carlson hosting Darryl Cooper of the Martyr Made Substack and his honest and accurate comments regarding Winston Churchill (more villain than hero) that sent vast segments of the 'alternative' Con Inc. Borg clutching their pearls and collapsing onto fainting chaises.

Special thanks to Notes From The Past for the enormous time and effort in gathering (obscure and rare) images and video clips, to bring this essay to life. I encourage all my readers to watch the fantastic short documentary of this post here:

Winston Churchill's relationship with the Jewish people and Zionist causes was significant throughout his political career. Historical examinations of the benefits of these relationships to his personal life—particularly of a financial nature—have been revealed in several published books since late last century, but other than David Irving, nobody connects them to his actions and motivations or dares to question his loyalties.

Why?

Sources:

Cohen, Michael J. Churchill and the Jews, 1900–1948. London: Frank Cass Publishers, 1985.

Gilbert, Martin. Churchill and the Jews: A Lifelong Friendship. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2007.

Irving, David. Churchill's War. London: Focal Point Publications, 1987.

Lough, David. No More Champagne: Churchill and His Money. London: Picador, 2015.

Makovsky, Michael. Churchill’s Promised Land: Zionism and Statecraft. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

Some people like Jews and some do not; but no thoughtful man can doubt the fact that they are beyond all question the most formidable and the most remarkable race which has ever appeared in the world.

— Winston Churchill

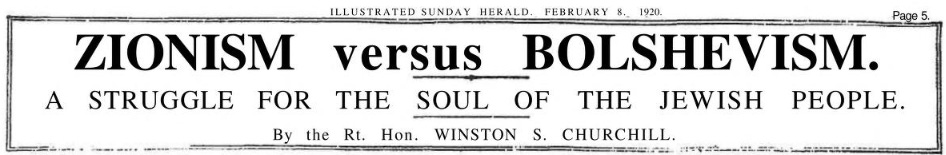

Zionism versus Bolshevism: Struggle for the Soul of the Jewish People

(1920)

Throughout his life, Churchill's engagement with the Jewish community spanned from early political involvement in representing his greater Manchester constituents in Stretford to later years as a staunch advocate for global Zionism, the political movement dedicated to creating a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

Churchill's ties to the Jewish people predated his birth. In 1841, his distant relative, Colonel Charles Henry Churchill, serving as the British Consul in Damascus for the Crown, was one of the first to propose the idea of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. In his 1841 proposal to the Ottoman authorities, he argued that the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine would bring economic development and political stability to the region, providing a buffer against regional instability and enhancing British strategic interests, decades before the formal Zionist movement led by Theodor Herzl took root.1

Winston's father, Lord Randolph Churchill, also had close ties with key Jewish figures, such as the Rothschild banking family and Sir Ernest Cassel, a prominent financier. These relationships had a profound impact on young Winston's worldview. Growing up surrounded by influential Jewish figures, Churchill came to believe that a nation's treatment of the Jews was directly linked to its moral standing and prosperity.2

In 1904, Churchill won a parliamentary seat representing Manchester North West, a constituency with a large Jewish population. He soon gained favor within this community by opposing the 1904 Aliens Act, which sought to limit Jewish immigration to Britain. This proposed legislation was a reaction to the influx of Jewish refugees fleeing persecution in Russia. Churchill’s strong stance against the Act helped him gain the trust and support of the Jewish electorate.3 It was also during this period that he developed a lasting friendship with Chaim Weizmann, a Russian-born Jewish chemist living in Manchester. Weizmann, who would later become the first president of Israel, was a leading advocate for Zionism, and his collaboration with Churchill played a pivotal role in shaping Churchill’s views on Jewish nationalism.4

Their collaboration led to the Balfour Declaration of 1917, in which the British government expressed its support for a Jewish national home in Palestine. This declaration was the result of coordinated lobbying by Zionist leaders, including Weizmann, the influence of Churchill, and significant financial backing from Jewish figures like the Rothschilds.

Churchill’s appointment as Colonial Secretary in 1921 brought him deeper into the complexities of the Middle East. After the San Remo Conference of 1920, the League of Nations granted Britain the mandate to implement the Balfour Declaration. As Colonial Secretary for the region, Churchill played a critical role in shaping policy in Palestine. In March 1921, he traveled to the region with T.E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia). During this visit, Churchill struck an agreement with Amir Abdullah, promising him control of Transjordan in exchange for non-interference with Zionist activities west of the Jordan River. This agreement effectively created the emirate of Transjordan, now known as Jordan. The deal was controversial—some Zionists felt betrayed by the partitioning of Palestine, while others saw it as a necessary compromise to secure Jewish land west of the river.5

Despite his attempts to balance conflicting promises to Jews and Arabs, Churchill faced significant pushback from Arab leaders. Soon after the creation of Transjordan, a group of Arab leaders presented a memorandum demanding an end to Jewish immigration, the abolition of the idea of a Jewish homeland, and the integration of Palestine with neighboring Arab nations. Churchill rejected these demands outright, asserting that the Jewish people had a legitimate historical connection to the land. He stated, "It is manifestly right that the Jews should have a national home. And where else could that be but in this land of Palestine, with which for more than 3,000 years they have been intimately and profoundly associated?"6

Churchill’s visits to Jewish settlements, such as Tel Aviv and Rishon LeZion, made a deep impression on him and reinforced his belief in the Zionist cause, motivating him to continue supporting Jewish immigration and land development, even as tensions in the region grew. He held no loyalties or admiration for Muslims or Arabs in the area and did little to hide this fact. His support for projects like harnessing the Jordan River for electricity drew criticism from the British aristocracy, many of whom felt that Churchill was giving in to excessive Jewish influence over British colonial policy. This led to debates in the House of Lords and efforts to curb Zionist influence.

Churchill took a strong stance against these attacks in the House of Commons, famously defending the Zionist hydroelectric project. He argued that without Jewish innovation, the land would remain barren and undeveloped. His passionate defense garnered enough support to override the opposition in the House of Lords, though the broader challenge of balancing Jewish and Arab interests in Palestine remained unresolved.7

In 1937, the British Peel Commission recommended partitioning Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states. While some Zionist leaders accepted this plan as a temporary compromise, Churchill was opposed, warning Weizmann that Britain could not be trusted to uphold such promises and urging caution.8

Churchill’s precarious finances were a constant challenge throughout his life. Despite his fame, he often teetered on the edge of bankruptcy due to extravagant spending on travel, gambling, and luxurious living. On his American tour in 1929, just before the stock market crash that led to the Great Depression, Churchill embarked on this trip to promote his book The Aftermath and deliver paid lectures. The book tour also served as an opportunity to establish connections with influential American figures.

During this trip, Churchill was hosted by media mogul William Randolph Hearst at his opulent San Simeon estate in California. Hearst, who controlled one of the largest newspaper empires in the world, became a key wartime ally. Churchill leveraged Hearst’s vast media monopoly to promote his political image in the United States and plant narratives favorable to Britain. Despite their differing political views, Hearst admired Churchill’s charisma and literary talent, while Churchill recognized the value of Hearst’s influence in shaping American public opinion.9 The visit also introduced Churchill to Hollywood elites, including Charlie Chaplin and Louis B. Mayer, during a luncheon at MGM Studios co-hosted by Hearst. These connections gave Churchill access to new opportunities to amplify his message through the latest mass media public relations medium—motion pictures.

Churchill’s America tour was also an opportunity to strengthen his connections to the Transatlantic Zionist cause. He met with Bernard Baruch and Otto Hermann Kahn, two influential American financiers, who played critical roles in aligning Churchill’s wartime efforts with the objectives of the American Zionist Congress. The Congress focused its vast financial resources on swaying American public opinion toward supporting Churchill and the British fight against Germany. This included orchestrating extensive public relations and propaganda campaigns in American media, to counter the prevailing isolationist sentiment, which stood at 93% in public opinion polls even into 1941. Baruch’s political connections and Kahn’s influence among New York’s elite later provided Churchill with essential backing, bridging his advocacy for Zionist interests with the strategic goals of Zionists, who held no loyalties to either Britain or The United States but remained steadfast in their singular goal of a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

Louis B. Mayer, the head of MGM Studios, was another influential figure Churchill engaged with during his 1929 tour. Mayer’s role in Hollywood provided Churchill with access to a new propaganda medium that would later serve British interests in swaying American opinion. While in Hollywood Churchill also met with silent film star Charlie Chaplin, dining with him on Hearst’s yacht. In October of 1940, Chaplin released his first “talkie film” The Great Dictator, a parody of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini. Despite previously writing and starring in over a hundred films, this was his most successful film at the box office.

Chaplin’s character, Adenoid Hynkle, the dictator of Tomania, despises Jews and collaborates with the dictator of Bacteria to take over the world. The film satirizes German propaganda, depicting concentration camps, and even references the use of gas, long before post-war Zionist and Bolshevik propaganda campaigns around the holocaust had been launched.

According to a Daily News Bulletin for March 18, 1931, from the Jewish Telegraph Agency located on Fleet Street in London, which carried daily news of the Jewish colonization of Palestine, Chaplin was born in London to Jewish immigrant parents with the surname Thorstein. However, there is no birth certificate confirming Chaplin’s ethnicity or birth name, and he seemed proud of letting the mystery of his origins confound MI5 and the FBI in later years as he became a target of red-baiting in the period known as McCarthyism. Despite its popularity and lasting legacy, The Great Dictator was never labeled British, American, or even Soviet propaganda. In speeches during the onset of the war, Chaplin called for a second western front, and he addressed audiences as "comrades" and praised their communist Soviet ally.

The timing of the film's release is no less curious. British and French forces had been embarrassed by Germany’s military, and run out of mainland Europe in a matter of weeks, which Churchill would later blame on French Generals. Churchill had returned to 10 Downing Street as Prime Minister the month prior, giving a series of now-infamous defiant speeches that summer that in retrospect through a historically accurate lens seem like the ravings of a mad lunatic intent on destroying the British Empire. The last of Hitler’s peace offerings—that insisted on Britain keeping her empire intact was supported by a majority of British civilians and half of Britain’s parliament and House of Lords. It was rejected by a stubborn and defiant Churchill, who replied with indiscriminate nightly bombing raids on Berlin.10

For weeks in August of 1940, Hitler still refused to target London or British cities, focusing only on British military targets. Churchill’s motives during these perilous few months are rarely brought into question at a time when peace was possible on favorable terms without the expansion of the conflict into a bloodthirsty affair that would cost another fifteen million lives on the European continent.

Later in the war, Churchill would also engage in firebombing campaigns targeting German refugees and civilians across dozens of cities, including the infamous two-night campaign on Dresden from February 13 to 15, 1945 which had no significant military targets. Nearly 150,000 civilians were burned alive during this incendiary bombing campaign, which remains one of the most controversial actions of the Allied forces during the war. Dresden was only filled with women, children, and Allied prisoners of war. Churchill's refusal to negotiate, dismissing any proposal that did not involve the destruction of Germany, led to an unnecessary prolonged war.

The answer to his motives may rest in Churchill’s so-called wilderness years of the 1930s, when he spent lavishly, incurred many debts, fueled his gambling addiction on a dozen holiday trips to the South of France, and found himself in dire straights when bankers in New York came calling for substantial losses owed from stock market speculation.

David Lough’s 2015 book No More Champagne: Churchill and His Money provides a detailed account of his precarious financial state and extravagant lifestyle. The book claims that throughout his career, Churchill struggled to balance his modest income as a public servant with his indulgent spending habits. Perhaps he knew his lifestyle and spending habits would always be backstopped by benefactors. By the 1930s, his debts exceeded £2.5 million in today’s money.

Churchill’s gambling losses were particularly egregious, with annual expenditures in the South of France amounting to the modern equivalent of £40,000 per trip, even while staying for free in lavish villas or on yachts. In 1927, while serving as Chancellor of the Exchequer, he lost £350—equivalent to £17,500 today—at a casino in Dieppe during a Mediterranean cruise. His spending extended to alcohol, with annual wine bills totaling £54,000 in today’s money, including £20,000 on champagne. Cigars were another significant expense, with monthly bills reaching £2000, debts that often went unpaid to his supplier for years.

In the summer of 1936, Churchill made two trips to the South of France, with an army of ghostwriters and secretaries in tow to complete his writing assignments for London newspapers and a book he was working on at the time. He bounced between the private yacht of Walter Guinness, the brewing magnate, and the private villas of anyone he could sponge off of, including one Hollywood starlet. He consumed copious amounts of expensive champagne and Napolean brandy. After another night of losses at the casino of Monte Carlo, he asked a British newspaper magnate Viscount Rothermere who paid him wild sums for weekly material that he outsourced to his ghostwriters, to bail him out with further “writing assignments.”

When that failed, he found a patron on holiday in the South of France in Hungarian Jewish film producer Alexander Korda (born Sándor László Kellner) who commissioned Churchill £4000 to write a screenplay for a film called Jubilee. Even when Korda knew it would never be produced, he kept Churchill “on contract” for any future scripts for his production studio London Films with the tidy annual stipend of £2000 or £120,000 in today's money. When war broke out Korda would return to Hollywood to produce films flattering the British cause to shift American public opinion away from isolationism.11

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 and subsequent crashes of the 1930s exacerbated Churchill’s financial woes, wiping out investments he had made in American stocks and oilfields. These extended beyond losses, to borrowed or leveraged investments estimated at £20,000 (approximately £1.2 million today), and deepened his financial woes. Renowned historian David Irving explains in his book Churchill’s War, that only with the intervention of Sir Henry Strakosch, a Jewish-Austrian financier who became wealthy from South African gold mines earlier in the century and had settled in the City of London, did Churchill narrowly avoid bankruptcy.12

Strakosch backstopped the Wall Street debts of £20,000, allowing him to retain his estate at Chartwell which he had put up for sale. Furthermore, Strakosch managed his money for him, sending him profits on his investments, and even agreed to cover his losses.13 While Churchill occasionally pledged to cut back on his spending, his lifestyle remained a constant source of financial excess, underscoring his dependence on wealthy benefactors to maintain both his public image and political career. From private investments to public gambling binges, it seems Churchill was always playing with house money.

Churchill’s ability to cultivate relationships with high-profile individuals ensured he never faced financial ruin. These included American financiers such as Bernard Baruch, Charles Schwab, and Otto Kahn, who stayed in contact with Churchill during these years. These connections reinforced Churchill’s network of transatlantic influence that would later be useful in turning the American people toward the British thirst for continued war.

According to most of Churchill's biographers, the 1930s were a difficult time as he faced political isolation, financial struggles, and an increased sense of identification with the Jewish cause, though he still took nearly a dozen holidays to the South of France, gambling excessively and only once returned a winner. When he wasn’t off gambling other people’s money, Churchill spent much of the decade at Chartwell, his country estate, which he managed with the help of financial support from Jewish allies like the Rothschilds and members of The Focus—a group of influential Jewish financiers and supporters.

David Irving dedicates chapter six of his book Churchill’s War to these subversive Jewish figures in the shadows of Churchill, opening with the following:

…shadowy groups had evolved in Britain and America, united by the aim of restoring the status quo in Germany. These now jointly and severally approached Mr Churchill. Their intervention came not a moment too soon for him. By the end of 1935, he had intimidating debts. No amount of writing dismantled his overdraft. It gnawed at his mind and distracted him from his work. He needed all the financial aid he could get. The president of the Anglo-Jewish Association, Leonard Montefiore, had begun sending him literature on the plight of the German Jews. But it was the Anti-Nazi Council, later known as the FOCUS, that would ensure Churchill’s political and financial survival.

Palestine is far too small to accommodate more than a fraction of the Jewish race, nor do the majority of national Jews wish to go there. But if, as may well happen, there should be created in our own lifetime by the banks of the Jordan a Jewish State under the protection of the British Crown, which might comprise three or four millions of Jews, an event would have occurred in the history of the world which would, from every point of view, be beneficial, and would be especially in harmony with the truest interests of the British Empire.

— Winston Churchill

Zionism vs Bolshevism

“A Home For The Jews” (1920)

1920: “…in harmony with the truest interests of the British Empire.”

1956: what British Empire?

In 1936, a critical turning point emerged in British political circles with the formation of The Focus, a group dedicated to opposing appeasement and advocating for British rearmament for war against Germany. This clandestine organization, funded heavily by wealthy Zionist backers like Sir Robert Waley-Cohen and Ben Cohen, worked closely with Winston Churchill to promote policies aligned with the Zionist cause and British preparedness for war.

Robert Waley Cohen, chairman of British Shell Corp., was a charismatic Zionist extrovert who would become, in the words of his biographer Robert Henriques, the dynamic force of The Focus. Waley Cohen, furnished the initial £50,000 (equivalent to £2.8 million today) to launch The Focus at a private dinner of prominent British Jews in July 1936.14 This sum allowed for significant political and media influence, including the recruitment of prominent journalists like Captain Colin Coote of The Times, who published pro-Focus pamphlets. The group's activities involved discreet lobbying of influential politicians, editors, and financiers to counter growing public sympathy for Nazi Germany in British and American newspapers and to galvanize support for zionist objectives.

Churchill, deeply embedded in The Focus, became a staunch ally of the Zionist movement during this period. His speeches increasingly emphasized Britain's obligations under the Balfour Declaration to support a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Chaim Weizmann the President of the World Zionist Organization, frequently met with Churchill, leveraging his political influence to advocate for increased Jewish immigration to Palestine and British support for Zionist terrorist groups in the region.

The Focus helped secure Churchill’s largest financial windfall to date—from a desperate Czechoslovakian government. The Munich Agreement on 30th of September, 1938 gave Hitler the Sudentenland and the following year saw Germany take Prague and turn all of Czechoslovakia into a protectorate.

According to David Irving in Churchill’s War, as tensions escalated with Germany, the Czechoslovak government, led by President Edouard Beneš, transferred large sums of money to their Embassy in London to bolster their diplomatic and political influence. They believed erroneously, as the Poles did, that the British Empire would guarantee their security. A total of £2 million (approximately £110 million in today’s value) was deposited into a private Midlands Bank account set up by Czechoslovakian Ambassador Jan Masaryk. This money was allocated, in part, to support The Focus in their efforts to challenge Neville Chamberlain’s government.

Before this windfall, Focus members were receiving £2,000 per annum (£120,000 today) from the Czechoslovakian government. Irving’s source for these transfers was a diary of a member of The Focus made available by Dr. Howard Gottlieb, director of the Mugar Memorial Library at Boston University. Irving also states, “Nazi intercepts of Beneš's secret telephone conversations with Osusky and Jan Masaryk confirm that senior British politicians were being paid by the Czechs in return for a promise to topple Neville Chamberlain’s government.”15

The funds were strategically disbursed to sway public opinion, finance media campaigns, buy members of Parliament, and secure the support of Winston Churchill. A portion of the funds, for example, £7,182 (about £429,000 today), was transferred into Czechoslovak Ambassador Jan Masaryk’s private account at Barclays Bank. However, after the war, when the Czechoslovakian government began investigating the fate of these substantial sums, they found that the details of the expenditures remained elusive. Masaryk refused to fully disclose how the money was spent, only citing the "unorthodox manner" in which it had been utilized.16

To the average Western historian, these substantial amounts underscore the extraordinary financial commitment Czechoslovakia made to safeguard its interests and resist Germany's rising threat. In retrospect, however, it represents something far more sinister—a rogue and subversive group within the halls of British power intent on installing their preferred Prime Minister in Churchill to avoid peace and continue on the path toward total continental destruction.

The financial support he received from The Focus also helped Churchill maintain his lifestyle. These substantial money transfers came in the aftermath of the March 1938 Nazi seizure of Baron Louis Nathaniel de Rothschild’s banking house in Austria, along with his subsequent arrest. The growing threat to European Jews in positions of financial prominence strengthened The Focus’ resolve against Hitler.

One key aspect of The Focus’s work with Churchill was its ability to provide timely and accurate information about the situation in Palestine and the broader Middle East. This included updates on the activities of Jewish terrorist organizations, the challenges posed by Arab opposition, and the internal dynamics of the British administration in the region. The Focus’ insights helped Churchill navigate these complexities and advocate for policies aligned with Zionist goals.

In 1939, the British government issued the White Paper, which severely limited Jewish immigration to Palestine and effectively reversed the Balfour Declaration. Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain defended the policy as necessary for maintaining stability in the Arab world, given Britain's strategic need for Middle Eastern oil. Churchill, however, condemned the White Paper as yet another act of appeasement, akin to the failed Munich Agreement.17

During this decade the Nazis were enacting the Haavara Agreement (1933-1938), which allowed the transfer of about 100,000 German Jews to Palestine along with their assets. This controversial agreement involved the Zionist Federation of Germany, the Anglo-Palestine Bank, and Nazi Germany. Although it offered a lifeline for Jews, attempts by Adolf Eichmann and Herbert Hagen to continue these transfers in 1938 were blocked by the British, underscoring the inconsistent British policy on Palestine. With Churchill out of power, he was helpless to intervene.

When Churchill returned to power in 1940 after Chamberlain’s resignation, he faced the immense task of leading Britain through World War II. However, his early tenure as Prime Minister was marked by the humiliating defeat of June 1940, when the British Expeditionary Force barely escaped annihilation at Dunkirk. Churchill remained stubbornly against accepting any of Hitler's proposals, though perhaps it wasn’t Churchill making these decisions.

He rejected any possibility of settlement and expressed his uncompromising stance regarding Germany's fate during a conversation with Sumner Welles, an American diplomat. Churchill declared that there could be "no peace without the total destruction of Germany," framing this as the only hope for civilization.18 But who’s civilization? Not the Poles or Czechs who put their faith and substantial financial sums in the hands of Churchill and British ministers only to be left to rot behind the oppressive Soviet Iron Curtain upon the conclusion of the “total destruction of Germany.”

Though his main focus was on destroying Germany, the plight of European Jews and the influences that surrounded him and maintained his affluent way of life can not be ruled out as motivating factors in many of his decisions. His personal secretary recalled seeing Churchill visibly moved when he learned of the Nazi treatment of Jewish Germans, lamenting, "Look what they're doing to my Jews." Despite his empathy and outrage, Churchill's capacity to help the Jewish people was constrained by wartime priorities and broader strategic considerations, mainly the need to lure the Americans into the war at all costs.

Throughout the war, Churchill maintained his support for Zionism, bolstered by continued backing from The Focus. However, the increasing tensions in Palestine were difficult to ignore. In 1946, the Jewish terrorist group Irgun bombed the King David Hotel, killing 91 people, including British citizens. This act of terrorism, along with other attacks on Palestinian villages, strained relations between the British authorities and the Zionist movement. Churchill, no longer in office, could do little as these events unfolded and his influence waned, though his sympathies for the Zionist cause were clear, particularly his support for arming Jewish settlers in Palestine to create a force capable of "undertaking their own defense."19

After World War II, Churchill’s influence continued to decline, especially after his defeat in the 1945 general election by Clement Attlee's Labour Party. Chaim Weizmann appealed to Churchill for help in establishing a Jewish state, but Churchill, now out of power, could not offer significant support. One year after the public farcical trials of Nuremberg, where confessions were obtained through torture, the State of Israel was declared, fulfilling the dream of organized Zionism that started the previous century on a parcel of Rothschild-purchased land within what was then the Ottoman Empire in 1829.

In his later years, Churchill reflected on his experiences during World War II and wrote his six-volume series, "The Second World War," published between 1948 and 1953. Despite covering the war in great detail, Churchill’s discussion of the Holocaust was minimal, with only a brief reference to the extermination of European Jews. He avoided terms like "gas chambers" or mentioning places like "Auschwitz," contributing to the early post-war selective memory of these atrocities.20

Churchill’s omission of the Holocaust didn’t draw criticism from historians at the time, because they had yet to be given the account of history that would later become the dominant popular narrative. The lack of any significant focus on a Jewish holocaust by Churchill was used as evidence for revisionist historians that what became the official Holocaust narrative was not an accurate reflection of historical events, but Soviet post-war propaganda, later utilized as a public relations ploy and Zionist leverage to benefit the newfound state of Israel financially.

The recognition of Israel by major world powers, including the United States and the Soviet Union, underscored the international significance of the event, but it also highlighted Britain’s waning influence on the global stage. The British Empire had in no uncertain terms been bankrupted by World War Two, with significant sums still owed to the United States.

Churchill returned to power briefly in the 1950s, serving as Prime Minister from 1951 to 1955. During his second tenure, he continued to express support for Israel, though his attention was largely focused on managing Britain’s declining power. Health problems marked his return to office, and he was increasingly frail by the time he retired from politics in 1955. Despite his declining health, Churchill’s legacy as an iconic figure in British politics has endured. His manufactured image as a heroic wartime leader persists as a symbol of the power and influence of Allied post-war propaganda.

Churchill died in 1965, leaving behind a confusing legacy, often shielded from criticism by prominent gatekeepers of information, and the purse strings they utilize to shield the public from uncomfortable historical truths. His advocacy for Jewish causes and Zionism was substantial, and relationships with influential Jewish figures such as Chaim Weizmann, the Rothschilds, and members of The Focus group were instrumental in shaping his views and actions. To say that Churchill’s legacy and policies in guiding Britain weren’t influenced by his financial dependence on key Jewish figures would be naive. His reliance on these figures opens him to criticism of the true motivations behind his many questionable decisions.

If you haven’t yet seen the fantastic documentary of this post by Notes From The Past, get on over there so we can do more of these in the future. (And substack really needs to enable videos within posts):

Watch: Historian David Irving on Hitler’s peace offer of June 1940, not long after the disaster at Dunkirk

Fixed Income Pensioner Discount (honor system)

Student Discount (valid .edu email)

Thank you for sharing

The Good Citizen is now on Ko-Fi. Support more works like this with one-time or monthly donations.

Donate

BTC: bc1qchkg507t0qtg27fuccgmrfnau9s3nk4kvgkwk0

LTC: LgQVM7su3dXPCpHLMsARzvVXmky1PMeDwY

XLM: GDC347O6EWCMP7N5ISSXYEL54Z7PNQZYNBQ7RVMJMFMAVT6HUNSVIP64

DASH: XtxYWFuUKPbz6eQbpQNP8As6Uxm968R9nu

XMR: 42ESfh5mdZ5f5vryjRjRzkEYWVnY7uGaaD

Michael Makovsky, Churchill’s Promised Land: Zionism and Statecraft (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 52.

Martin Gilbert, Churchill and the Jews. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2007, pp. 14-16.

Ibid., 31-33.

Makovsky, Churchill's Promised Land, 59–61

Gilbert, Churchill and the Jews, 90-92.

Makovsky, Churchill’s Promised Land, 115–117

Gilbert, Churchill and the Jews, 93.

Michael J. Cohen, Churchill and the Jews, 1900–1948 (London: Frank Cass Publishers, 1985), 173–174.

Ibid., 175; Gilbert, Churchill and the Jews, 95–96; Makovsky, Churchill’s Promised Land, 161–162.

David Irving, Churchill’s War: The Struggle for Power. London: Focal Point Publications, 2003, pp. 440–443.

Ibid., 35–37, 98–99.

Ibid., 52-53.

Ibid., 59–60, 432–434.

Ibid., 64–65.

Ibid., 63-65

Ibid., 100.

Makovsky, Churchill's Promised Land, 164; Gilbert, Churchill and the Jews, 271.

Irving, Churchill’s War, 239.

Cohen, Churchill and the Jews 1900–1948, 312; Makovsky, Churchill’s Promised Land, 232; Gilbert, Churchill and the Jews, 270.

Gilbert, Churchill and the Jews, 287-288; Cohen, Churchill and the Jews 1900–1948, 15-16.

Substack is a s**t show Good Citizens! Unfortunately, the link to Notes From The Past's fantastic short documentary of this post ended up as a URL because we scheduled to publish at the same time, and not an embedded post or video. Substack still hasn't even enabled embedded videos for some reason. He spent many hours putting it together, uncovering rare film footage and photos that really bring these words to life. Please check out the documentary. You'll be glad you did...

https://notesfromthepast.substack.com/p/churchill-and-the-focus?

An excellent description of the truth about the degenerate, perfidious, mendacious and malevolent drunkard Winston Churchill, who because of his incompetence had to be removed from most of the posts he was given. He was directly responsible for the death of hundreds of thousands of his own people and the difference between his "reputation" and the truth is breathtaking.